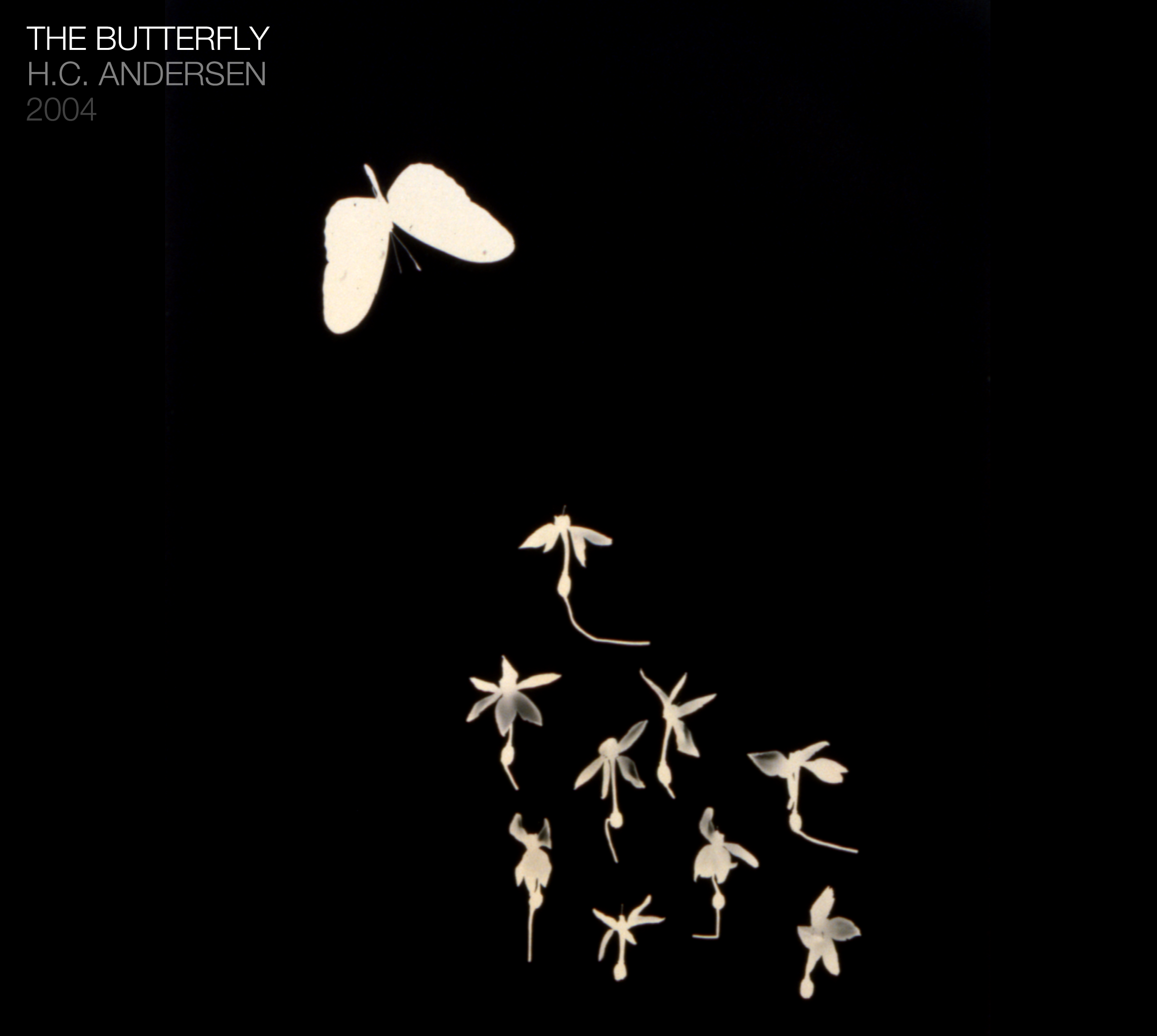

The Butterfly (1860)

The butterfly wanted a sweetheart, and naturally he wanted one of the prettiest of the dear little flowers. He looked at each of them; there they all sat on their stalks as quiet and modest as little maidens ought to sit before they are engaged; but there were so many to choose from that it would be quite difficult to decide. So the Butterfly flew down to the Daisy, whom the French call “Marguerite.” They know she can tell fortunes. This is the way it’s done: the lovers pluck off the little petals one by one, asking questions about each other, “Does he love me from the heart? A little? A lot? Or loves he not at all?” – or something like that; everyone asks in his own language. So the Butterfly also came to ask, but he wouldn’t bite off the leaves; instead he kissed each one in turn, thinking that kindness is the best policy.

“Sweet Miss Marguerite Daisy,” he said, “you’re the wisest woman of all the flowers – you can tell fortunes! Tell me, should I choose this one or that one? Which one am I to have? When you have told me, I can fly straight to her and propose.”

But Marguerite answered not a word. She resented his calling her “a woman,” for she was unmarried and quite young. He put his question a second time, and then a third time, and when he still get a word out of her he gave up and flew away to begin his wooing.

It was early spring; the snowdrops and crocuses were growing in abundance. “They’re really very charming,” said the Butterfly. “Neat little schoolgirls, but a bit too sweet.” For, like all very young men, he preferred older girls. So he flew to the anemones, but they were a bit too bitter for his taste. The violets were a little too sentimental, the tulips much too gay. The lilies too middle class, the linden blossoms too small, and, besides, there were too many in their family. He admitted the apple blossoms looked like roses, but if they opened one day and the wind blew they fell to pieces the very next; surely such a marriage would be far too brief. He liked the sweet pea best of all; she was red and white, dainty and delicate, and belonged to that class of domestic girl who is pretty yet useful in the kitchen. He was about to propose to her when he noticed a pea pod hanging near by, with a withered flower clinging to it. “Who’s that?” he asked.

“It’s my sister,” said the pea flower.

“Oh, so that’s how you’ll look later on!” This frightened the Butterfly, and away he flew.

Honeysuckles hung over the hedges; there were plenty of those girls, long-faced and with yellow complexions. No, he didn’t like that kind at all. Yes, but what did he like? You ask him!

Spring passed and summer passed; then autumn came, and he was still no nearer making up his mind. Now the flowers wore beautiful, colorful dresses, but what good did that do? The fresh, fragrant youth had passed, and it is fragrance the heart needs as one grows older; and of course dahlias and hollysocks have no particular fragrance. So the Butterfly went to see the mint.

“It’s not exactly a flower – or rather it’s all flower, fragrant from root to top, with sweet scent in every leaf. Yes, she’s the one I want!” So at last he proposed to her.

But the mint stood stiff and silent, and at last said, “Friendship, if you like, but nothing else. I’m old, and you’re old, too. It would be all right to live for each other, but marriage – no! Don’t let’s make fools of ourselves in our old age!”

And so the Butterfly did not find a sweetheart at all. He had hesitated too long, and one shouldn’t do that! The Butterfly became an old bachelor, as we call it.

Now it was a windy and wet late autumn; the wind blew cold down the backs of the poor trembling old willows. And that made them creak all over. When the weather is like that it isn’t pleasant to fly about in summer clothing, outside. But the Butterfly was not flying out-of-doors; he had happened to fly into a room where there was a fire in the stove and the air was as warm as summer. Here he could at least keep alive. “But just to keep alive isn’t enough,” he said. “To live you must have sunshine and freedom and a little flower to love!”

And he flew against the windowpane, was noticed by people, admired, and set on a needle to be stored in a butterfly collection. This was the most they could do for him.

“Now I’m sitting on a stalk, just like the flowers,” said the Butterfly. “It isn’t very much fun; it’s just like being married, you’re bound up so tightly!” He comforted himself with this reflection.

“A poor consolation, after all,” said the pot plants in the room.

“But you can’t take the opinion of pot plants,” thought the Butterfly. “They converse too much with human beings!”

By H.C. Andersen (1860). Translation by Jean Hersholt, published in The Complete Andersen (New York, 1949).